作者: Uliana Vasilachi

日期: 07.12.2022

Prolonged wearing of a NIV mask may lead to patient discomfort and pressure injuries.

A pressure injury is defined as "localized damage to the skin and underlying soft tissue usually over a bony prominence or related to a medical or other device. The injury can present as intact skin or an open ulcer . . . [and] occurs as a result of intense and/or prolonged pressure or pressure in combination with shear" (Edsberg et al., 2016).

In order to protect your patient’s skin, you can reduce the risk of pressure injuries (also known as pressure ulcers) during noninvasive ventilation by carefully selecting a suitable NIV mask and by taking precautionary steps.

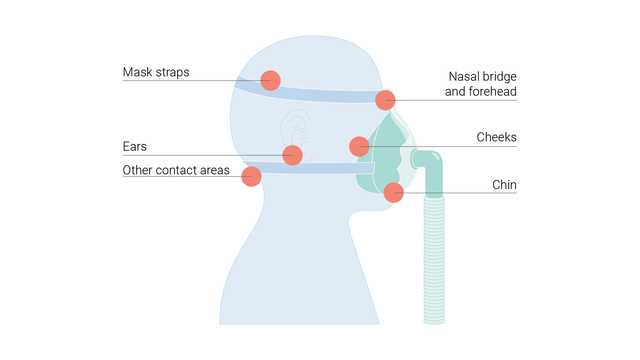

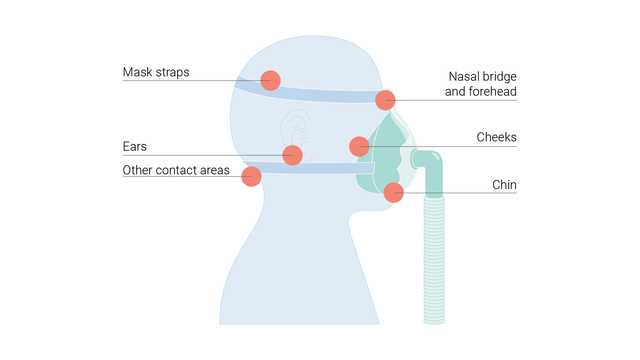

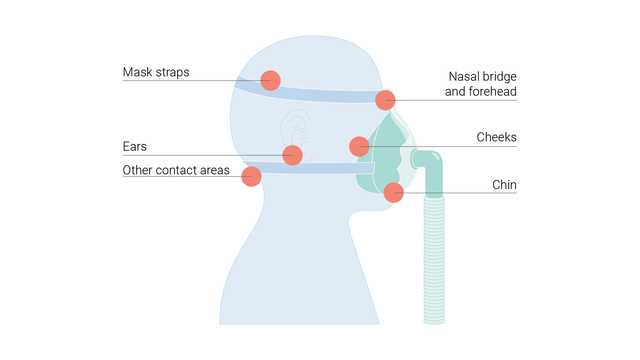

These injuries can occur as a result of pressure on the skin over a bony prominence. Patients receiving respiratory support using a mask may develop pressure ulcers on different parts of the face, including the forehead, cheeks, chin, and bridge of the nose, where they are most common.

There are various reasons why a patient may develop pressure injuries:

Severe patient discomfort can be prevented by spotting a pressure injury early in its development.

Firstly, the patient’s facial anatomy should be assessed. Does the patient have any facial anomalies? Which mask configuration is better suited to the treatment and will promote greater breathing comfort? It is important to select the most suitable size and type of mask for the individual patient. This not only helps prevent leakage, it can also guard against possible pressure injuries.

During the treatment, the patient’s skin should be kept clean and dry to help reduce friction from the mask. It is crucial to examine the placement of patient’s mask regularly for early signs of pressure points. If there is skin irritation, hydration and moistening of the affected area can speed up the recovery. If the patient can tolerate a break from the oxygen, stop the therapy for 10 minutes. It is also advisable to either reposition the mask or change to a different mask configuration at regular intervals. A different mask configuration will relieve the pressure from the previous mask and let the wounds heal. It is important to check regularly for the signs:

Commonly used types of masks are nasal, full face, or helmet masks. Hamilton Medical offers a wide range of interfaces in different configurations and sizes.

Full citations below: (

了解无创通气的优点和临床相关性,以及有关选择正确连接界面、调节设置和监测患者的实用信息。