Автор: Жан-Мишель Арналь, старший реаниматолог, больница Hopital Sainte Musse, Тулон, Франция

Дата: 19.10.2018

Last change: 09.09.2020

FormattingНедавнее физиологическое исследование показало, что пищеводное давление определяет плевральное давление в середине грудной полости при всех уровнях PEEP. Таким образом, абсолютное измерение пищеводного давления помогает при установке значения PEEP и мониторинге транспульмонального давления.

Так как же следует правильно измерять пищеводное давление?

Пищеводный баллон необходимо правильно расположить и наполнить воздухом, а затем следует проверить его размещение.

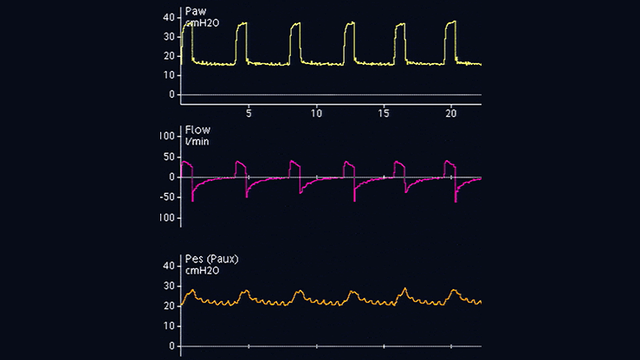

Оптимальное положение пищеводного баллона – нижняя треть пищевода, расстояние от ноздрей – 35–45 см. Пациент должен находиться в положении полулежа. Пустой баллон сначала вводится в желудок, расположенный примерно в 50–60 см от ноздрей. Баллон наполняют воздухом до стандартного объема (1 мл для катетера CooperSurgical и 4 мл для катетера Nutrivent). Во время вдоха внутрижелудочное давление имеет положительное отклонение как у пассивных, так и у спонтанно дышащих пациентов. Положение желудка проверяют путем аккуратного нажатия руками на эпигастральную область, вследствие чего внутрижелудочное давление сразу повышается (см. рисунок 1).

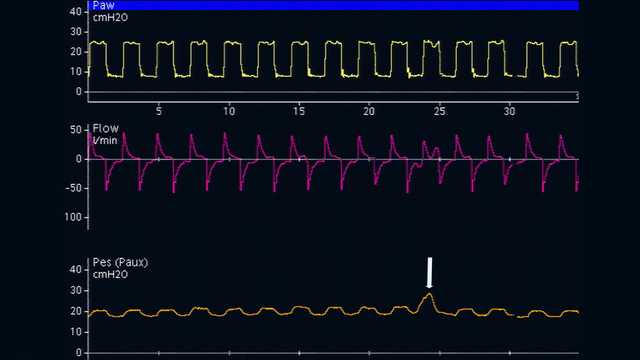

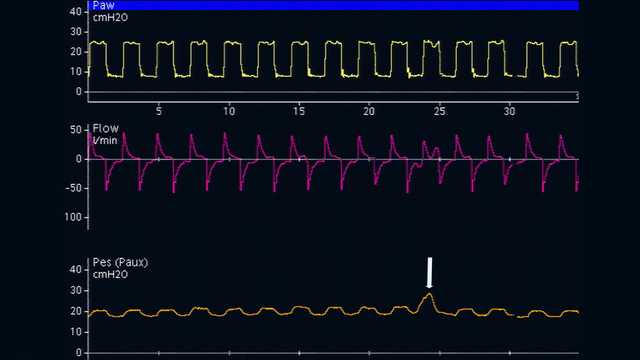

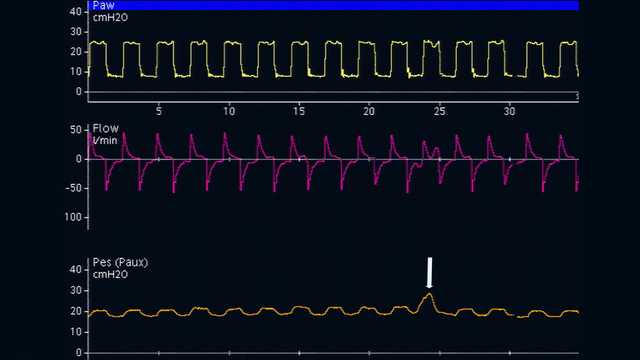

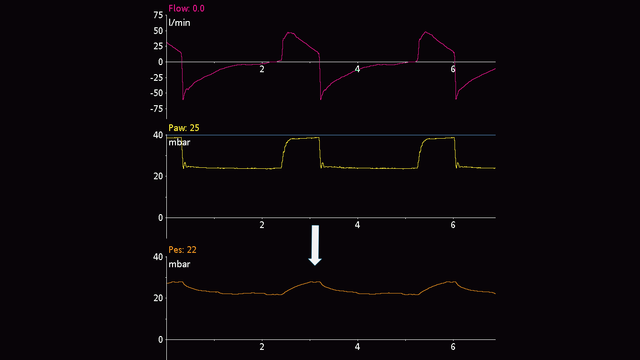

Затем пищеводный катетер осторожно извлекают, пока баллон все еще наполнен, чтобы расположить баллон в нижней трети пищевода. При переходе от внутрижелудочного давления (см. рисунок 2) к пищеводному (см. рисунок 3) давления исходная линия кривой давления меняется, и отображает сердечные осцилляции.

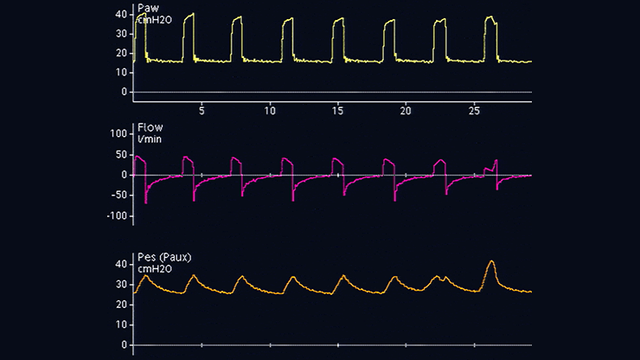

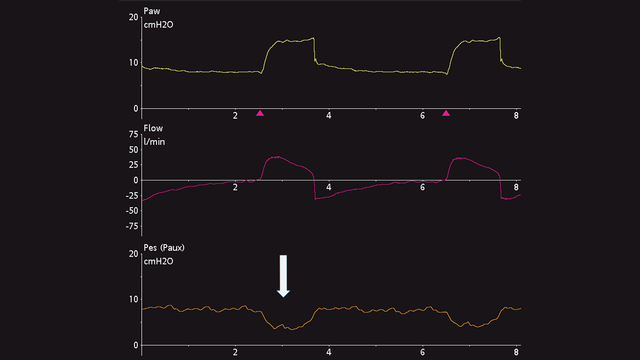

Отклонения пищеводного давления положительны во время вдоха у пассивных пациентов (см. рисунок 4), но отрицательны у пациентов со спонтанным дыханием (см. рисунок 5). Если сердечные осцилляции искажают сигнал пищеводного давления, можно извлечь катетер еще на 2–5 см.

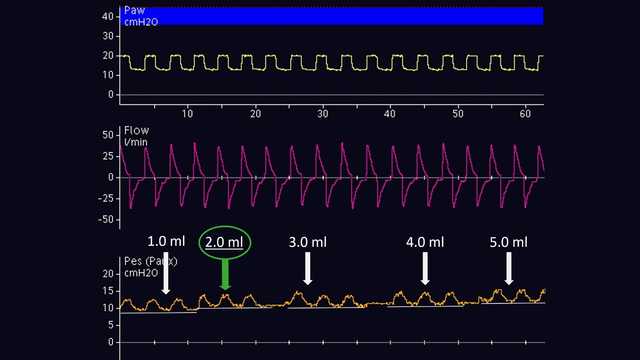

Объем воздуха для правильного наполнения баллона следует титровать индивидуально. Это возможно только у пассивных пациентов. Согласно методу, предложенному Моджоли и др. в 2016 г., баллон наполняют на 0,5–3 мл с постепенным шагом 0,5 мл для катетера Cooper Surgical и на1–8 мл с шагом 1 мл для катетера Nutrivent (см. рисунок 6). Во время постепенного наполнения баллона исходное пищеводное давление увеличивается, а величина отклонения пищеводного давления изменяется. Правильный объем наполнения определяется по наибольшему отклонению пищеводного давления. Если при двух разных объемах наполнения величина отклонения пищеводного давления одинакова, выбирается наименьший объем наполнения.

После правильного расположения баллона в пищеводе и его наполнения проводится контрольная проверка наличия окклюзии. При проверке дыхательные пути перекрывают в конце выдоха, чтобы изменить давление в них, а затем проверяют, изменилось ли пищеводное давление на ту же величину.

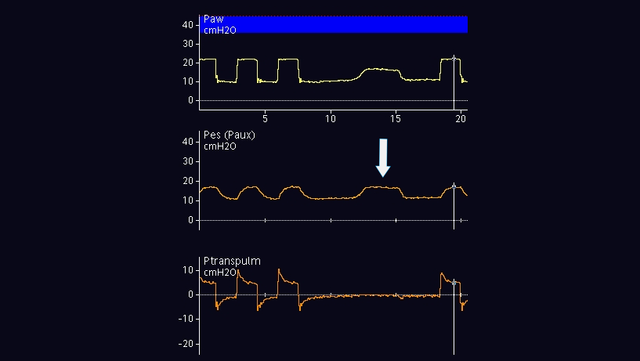

У пассивных пациентов можно выполнить окклюзию в конце выдоха. Когда клапан выдоха закрыт, сожмите грудную клетку руками с обеих сторон, чтобы увидеть положительное отклонение давления в дыхательных путях и пищеводе. Величина повышения давления в дыхательных путях и пищеводе должна быть одинаковой. Другими словами, транспульмональное давление не должно изменяться (см. рисунок 7).

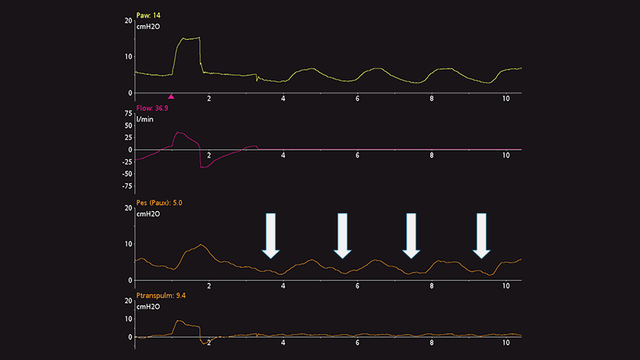

У активных пациентов проверка наличия динамической окклюзии также включает окклюзию в конце выдоха. Нет необходимости сжимать грудную клетку руками, так как во время окклюзии пациент будет совершать спонтанное дыхательное усилие. Результатом является отрицательное отклонение давления в дыхательных путях и пищеводе. Величина снижения давления в дыхательных путях и пищеводе должна быть одинаковой, т. е. транспульмональное давление не должно изменяться (см. рисунок 8).

Если требуется постоянно контролировать пищеводное давление, необходимо повторно проверить правильность размещения и объем наполнения баллона.

Полный список цитируемых материалов см. ниже: (

Клинически проверенные рекомендации касательно того, что следует делать и чего следует избегать при измерении пищеводного давления у пациентов с острым респираторным дистресс-синдромом.